Why India’s Public Wi-Fi Dream Is Still Buffering

As mobile data gets costlier and patchy in rural India, the government’s public Wi-Fi plan — PM WANI — faces resistance from telcos and regulatory roadblocks.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, many students across India were forced to rely on mobile data to attend school. In theory, India’s expanding 4G network was meant to keep them connected. In practice, it often did not.

In Uttarakhand’s remote Bangaan region, students routinely trekked 10–12 kilometres to reach a hilltop in Kotadhar just to catch a usable mobile signal, beamed not from Uttarakhand but from neighbouring Himachal Pradesh.

For thousands of students in semi-rural and low-connectivity regions, 4G wasn’t enough. At the time, higher-speed 5G networks weren’t yet available since India’s 5G rollout only began in mid-2022 and reached many cities only through 2023. Students reported poor signal strength, frequent call drops, and unstable data connections.

This was one of the clearest signals of India’s internet divide — not in terms of devices or SIM cards, but in terms of latency, affordability, and last-mile reliability. It was also the very gap that the government’s public Wi-Fi initiative, Prime Minister Wi-Fi Access Network Interface (PM-WANI), was designed to bridge.Years later, public Wi-Fi remains crucial for India’s digital...

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, many students across India were forced to rely on mobile data to attend school. In theory, India’s expanding 4G network was meant to keep them connected. In practice, it often did not.

In Uttarakhand’s remote Bangaan region, students routinely trekked 10–12 kilometres to reach a hilltop in Kotadhar just to catch a usable mobile signal, beamed not from Uttarakhand but from neighbouring Himachal Pradesh.

For thousands of students in semi-rural and low-connectivity regions, 4G wasn’t enough. At the time, higher-speed 5G networks weren’t yet available since India’s 5G rollout only began in mid-2022 and reached many cities only through 2023. Students reported poor signal strength, frequent call drops, and unstable data connections.

This was one of the clearest signals of India’s internet divide — not in terms of devices or SIM cards, but in terms of latency, affordability, and last-mile reliability. It was also the very gap that the government’s public Wi-Fi initiative, Prime Minister Wi-Fi Access Network Interface (PM-WANI), was designed to bridge.Years later, public Wi-Fi remains crucial for India’s digital inclusion story. But despite ambitious goals, PM-WANI has struggled to scale up, facing resistance from telecom operators, high infrastructure costs, and regulatory hurdles. As data costs rise and mobile networks show cracks, the case for affordable, community-driven Wi-Fi has only grown stronger.

TRAI’s Public Wi-Fi Vision From 2016

The idea of PM-WANI wasn’t born overnight. The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) first floated the concept of creating a decentralised public Wi-Fi ecosystem back in 2016. At the time, India had just 31,518 public Wi-Fi hotspots — compared to over 47 million globally. TRAI estimated that for India to have even one hotspot per 150 people, it would need at least 800,000 hotspots. The gap was stark: globally, Wi-Fi hotspots had grown by 568% between 2013 and 2016. India, meanwhile, had managed just a 12% increase.

Later that year, in November 2016, TRAI laid out a more detailed framework suggesting how different stakeholders — telcos, Internet Service Providers (ISPs), payment gateways and communities — could collaborate and divide the operational cost of running a hotspot.

By March 2017, TRAI formalised the model in another paper that introduced the roles of Public Data Offices (PDOs) and Public Data Office Aggregators (PDOAs). Under this structure, telcos and ISPs could monetise bandwidth by selling it to PDOs, while PDOs — often small shopkeepers — could earn by reselling affordable, sachet-sized internet packs to local users. The idea was to make public Wi-Fi both commercially viable and accessible.

Telcos Charged Lakhs, Small Players Backed Out

Today, PM-WANI has around 3.33 lakh public Wi-Fi hotspots across the country. But that’s still a fraction of its original ambition: 10 million hotspots by 2022, and an earlier goal of 50 lakh by 2020.

A key reason has been resistance from telecom companies. Initially, PDOs like small shops, supermarkets, or just entrepreneurs interested in making revenue from the PM-WANI model had to purchase commercial bandwidth from an ISP — often via an Internet leased line or business broadband plan—because ISPs treated PM-WANI as a commercial resale model.

These leased lines were prohibitively expensive, with telecom operators reportedly charging up to Rs 8 lakh a year for a 100 Mbps line, according to Financial Express. This made breakeven impossible for small PDOs. Combined with limited fibre access in some areas and a general lack of awareness among potential operators, PM-WANI’s expansion has struggled to reach critical mass.

“The slow adoption of PM-WANI is primarily due to exorbitant internet bandwidth charges imposed, driven by predatory pricing by telcos and ISPs,” T.V. Ramachandran, president of the Broadband India Forum (BIF), told The Core.

“The shortfall in meeting targets can also be attributed to high backhaul costs from expensive leased-line connections, and especially, to certain vested interests who have consistently advocated against the importance of public Wi-Fi.”

TRAI Steps In, Telcos Push Back

In response, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) stepped in. In June 2025, it issued an order capping the wholesale rates that telecom operators and ISPs can charge PDOs. Under the new rule, retail fibre-to-home (FTTH) plans with speeds up to 200 Mbps must be made available to PDOs at no more than twice the applicable retail tariff. The move was intended to prevent ISPs from charging exorbitant “commercial” rates and bring PM-WANI bandwidth costs in line with home broadband pricing.

Telecom companies had strongly opposed such intervention. TRAI, however, rejected calls to scrap the scheme and instead moved to reduce input costs. The Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI), which represents major mobile players, argued that only licensed operators or their franchisees should be allowed to offer Wi-Fi services—otherwise, it would violate the Indian Telegraph Act.

Bharti Airtel and Vodafone Idea echoed these concerns, pointing to right-of-way hurdles in laying fibre and questioning the need for a parallel unlicensed Wi-Fi network. Telcos also contended that Wi-Fi should be treated as a localised offload solution rather than an alternative to mobile data.

Public Wi-Fi Still Has Its Place

Experts, however, have also countered the telcos' argument, stating that public Wi-Fi doesn’t compete with mobile — it complements it.

“Wi-Fi hotspots are essential to offload high-bandwidth activities like video streaming and app updates, freeing up capacity on mobile networks and improving user experience,” Ramachandran of BIF added.

As NK Goyal, chairman emeritus of the Telecom Equipment Manufacturers Association of India, pointed out, even in dense cities like Delhi, signal dropouts are common. “In high-footfall zones like malls, airports, and railway stations, cellular networks often struggle due to congestion, making reliable Wi-Fi a useful alternative,” he told The Core.

Even at a national scale, mobile connectivity isn’t as comprehensive as it seems. “Even with widespread cellular coverage, roughly half of Indians remain offline,” the Broadband India Forum (BIF) told The Core. “India’s tele-density has plateaued at around 84%, and rural areas lag far behind at just 58%,” Ramachandran of BIF said.

BIF also noted that 4G and 5G face limitations in spectrum propagation, distance from towers, and network congestion. Despite increased mobile data availability, usage per subscriber has flattened at 21GB. Only 23% of users have adopted 5G, while 72% still rely on 4G handsets, and according to BIF, this signals that mobile data is not a one-size-fits-all solution for digital access.

Public Wi-Fi’s Moment May Yet Come

The cost gap is no longer academic. With major telcos announcing sharp hikes in mobile tariffs, the affordability question has come back into focus. For many low-income users, even subsidised 4G or 5G plans are becoming out of reach.

“Mobile tariffs have been rising, and are projected to rise further in the coming years, as telecom operators seek revenue stability to sustain their operations,” T.V. Ramachandran, president of the Broadband India Forum, told The Core.

This is where PM-WANI and other public Wi-Fi models can play a vital role. “PM-WANI is a critical enabler for citizens at the bottom of the pyramid,” Ramachandran said, “by offering low-cost access through small-value vouchers priced as low as Rs 5 or Rs 10.”

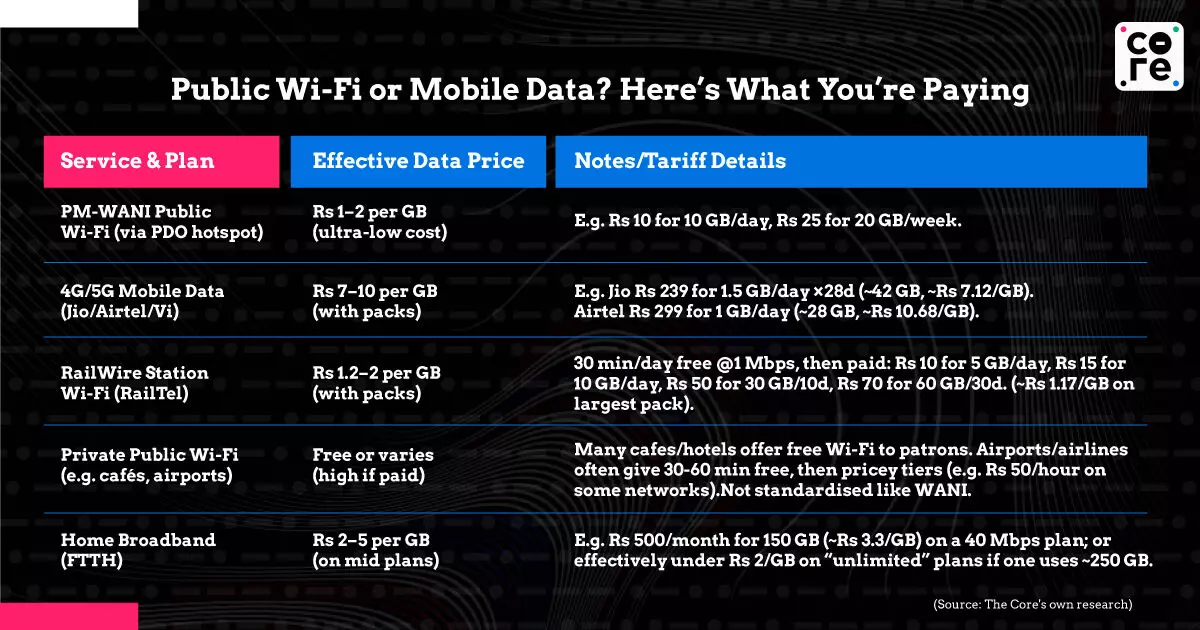

The affordability advantage is clear: while mobile data can cost Rs 7–10 per GB, PM-WANI and RailTel Wi-Fi often offer data at Rs 1–2 per GB, according to The Core’s research.

For advocates of public Wi-Fi, the path forward is not about choosing between cellular networks and PM-WANI—it’s about recognising their respective roles in a country as large and digitally uneven as India.

“We cannot cover 2.6 billion people globally, and India too cannot be fully covered by cellular networks alone,” said Goyal, of the Telecom Equipment Manufacturers Association of India, He argues that public Wi-Fi remains essential to fill these digital voids, particularly for services that now underpin daily life such as UPI payments, online banking, ticketing, telemedicine, and education.

While telcos continue to argue that PM-WANI undercuts their pricing and creates indirect competition, Goyal rejects this view. “This Wi-Fi is in no way on the revenue of telecom operators. It will give them more revenue because people will be able to use more Wi-Fi, and then more revenue goes to them.”

For now, PM-WANI may still be running behind its targets. But with mobile data getting costlier, network quality remaining uneven, and digital dependence growing, India’s public Wi-Fi moment may still be ahead of it.

As mobile data gets costlier and patchy in rural India, the government’s public Wi-Fi plan — PM WANI — faces resistance from telcos and regulatory roadblocks.