India’s Helicopter Industry Hovers Between Promise and Policy Paralysis

India’s civil helicopter industry has all the elements that it needs to take off but remains weighed down by fragmented policy and skeletal infrastructure

The Gist

The launch of India's first private helicopter assembly line in Karnataka marks a significant step for the country's civil helicopter industry, which faces regulatory challenges.

- Joint initiative by Airbus and Tata Advanced Systems aims to manufacture H125 helicopters.

- Potential growth in the sector is hindered by fragmented policies and infrastructure.

- Operators emphasise the need for improved regulatory frameworks and infrastructure to unlock the market's vast potential.

When India’s first private helicopter assembly line was launched this year in Karnataka’s Vemagal, it was more than just a milestone in manufacturing. It hinted at a new beginning for a sector that has long been mired down by regulatory turbulence.

The joint initiative between Airbus and Tata Advanced Systems Ltd. (TASL) to manufacture H125 single-engine helicopters brings potential for growth amidst regulatory uncertainties.

This comes as India gears up to manufacture civil helicopters for local, para-public, and international sales, with Mahindra Aerospace handling the production of fuselages.

India’s civil helicopter industry has all the elements that it needs to take off — manufacturing ambition, urgent demand across tourism, energy, and medical services. The sector, however, remains weighed down by fragmented policy and skeletal infrastructure. After years of being stalled, will India’s helicopter segment truly have its moment?

India’s Helicopter Leap

Manufacturing helicopters in India has immediate and long-term gains such as lower acquisition costs, reduced import dependence and stronger supply chains through technology transfer. “This is a strategic extension of our aerospace capabilities,” said Sukaran Singh, CEO of Tata Advanced Systems Limited, had said. Meanwhile, Airbus India head Jürgen Westermeier had said, “India is an ideal helicopter country. A ‘Made in India’ helicopter will help develop this market and position helicopters as an essential tool for nation-building.”

The first deliveries are expected by early 2027, with plans to scale production based on regional demand. Airbus has also signed an MoU with the Small Industries Development Bank of India to ease financing for civil helicopter operators — a hurdle that has existed for a long time in the capital-heavy business.

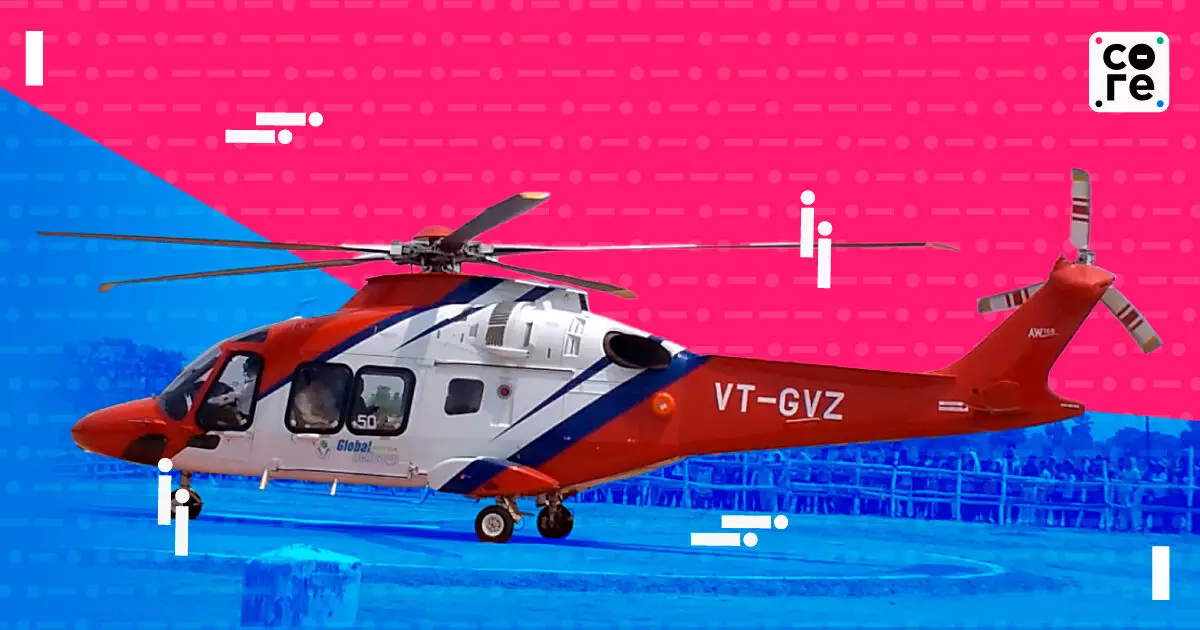

From ferrying pilgrims to Kedarnath and Amarnath, to supporting offshore oil operations in Mumbai High and Krishna Godavari Basin, helicopters have quietly served a vital role in mobility. Operators like Pawan Hans, Global Vectra, and Heritage Aviation dominate this space, yet the sector’s vast potential remains untapped.

Rohit Kapur, co-founder of The Jet Company and former president of the Business Aircraft Operators Association (BAOA), a key advocacy body for India's general and business aviation sector, had said during a recent conference, “Helipads and heliports are dependent on policy push, and infrastructure is the responsibility of the government. Helicopter operators can only push to a limited extent.”

Even the Director General of Civil Aviation, Faiz Ahmed Kidwai, admitted at a recent BAOA conference, “A lot more could have been done. The potential has not been achieved. In a country where people use helicopters for weddings, we can do much more.”

Helicopter Policy Needs Lift-Off

Despite the DGCA’s launch of a Helicopter Directorate in June, India’s rotor-wing sector remains stalled by fragmented oversight, rigid regulations, and patchy infrastructure. Fragmented oversight among the Civil Aviation Ministry, DGCA, Airports Authority of India, Defence Ministry, and state governments delays every clearance—from helipad licensing to route permissions.

The results are visible. Most helipads lie unused, and helicopters face restricted routing and landing options. Frequent accidents in mountainous regions driven by poor meteorological support and limited pilot training underscore systemic gaps.

Public perception hasn’t helped either. Helicopters are still seen as for use by the elite or during emergencies rather than essential public infrastructure. while high capital costs and scarce leasing options deter operators.

Rules also vary widely by cities and regions. Pune and Chhattisgarh permit take-offs from airports and private land, while Delhi and Mumbai impose tight restrictions due to security sensitivities. “We need rooftop helipads like Brazil and hospital-based landing zones for emergencies,” said Kapur, citing São Paulo’s 2,200 daily helicopter movements and 260 helipads, clocking a landing every 45 seconds.

Landing at the busy Delhi airport is a bureaucratic marathon. Naveen Jindal, chairman of Jindal Steel and Power, suggested: “We have large polo fields where we can land. In Kurukshetra, we should be allowed night take-offs.”

For all the talk of mobility, India’s promise of a “helicopter in every district” has faded, overshadowed by road-building priorities, said Kapur.

With just 250 civilian helicopters serving 1.4 billion people, vertical mobility remains out of sync with the country’s topography. Remote Himalayan hamlets and flood-prone deltas remain stranded not by terrain but by policy inertia. Unlocking this potential will required a unified, single-window framework. For now, that remains a distant dream.

India’s Lifesaving Link?

The 2021 Heli-Disha guidelines identified 10 cities and 82 routes to streamline helicopter corridors and helipad approvals, but rollout has been bumpy. Four years later, progress has sputtered. Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) remain tangled in regulatory fog. The DGCA mandates costly multi-engine, IFR-certified models, shrinking affordability for operators trying to serve rural India.

Without integrated rules for air ambulance ops, crew training, and medical coordination, operators face regulatory fog and logistical gridlock, operations remain patchy.

When AIIMS Rishikesh Sanjeevani, India’s first helicopter ambulance service- in October 2024 in Uttarakhand, there was much optimism.

“We need a policy that allows helicopter ambulances to be treated like ICUs in the sky,” Dr Madhur Uniyal, nodal officer for Sanjeevani had said. Yet, the initiative was grounded after tail rotor accident in May.

Most insurers do not reimburse air ambulance costs, and DGCA regulations restrict landing flexibility. Without a clear reimbursement model, operators struggle to sustain services.

Kapur said that India could absorb 500–600 dedicated EMS helicopters to meet national demand if norms were eased.

Sudhir Rajeshirke, president Aerospace at Jubilant Enpro, regulatory bottlenecks and not funding as the problem that held up projects, often at the induction phase.

Rajeshirke cited the example of a healthcare firm that sought helicopter services to be outsourced to a specialised management company, something that is currently not permitted in India. The project was ultimately withdrawn.

Expressways And Emergency Helipads

One area that has shown promise in the sector is India’s where helipads are being or medical and disaster response. The 1,350-km Delhi-Mumbai Expressway will host 12 helipads across Rajasthan — six in Sawai Madhopur, four in Dausa, two in Kota — positioned to ensure trauma-care access within the “golden hour.”

Similarly, the 1,257-km Amritsar-Bathinda-Jamnagar Expressway aligns with eight airports and multiple defence bases, bringing refineries, thermal plants, and ports within rotor range. Though exact heliport sites remain undisclosed, the plan signals a shift: India’s high-speed corridors are evolving into dual-use lifelines, marrying road and air rescue capabilities.

UDAN: Promise Amid Patchiness

Expanding the UDAN scheme, which is meant to democratise aviation and improve access, to include helicopter services marked a strategic shift, targeting remote, hilly, and tribal regions underserved by fixed-wing aircraft.

By 2025, 15 heliports will link Himachal, Uttarakhand, the Northeast, and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Operators like Pawan Hans, Heritage Aviation, and Global Vectra are already flying missions for tourism, tribal outreach, and medical aid.

But restrictions persist. India restricts single-engine helicopter operations in hilly terrain, favouring twin-engine models due to safety concerns, though this policy is increasingly debated. “We are killing our own market by restricting our infrastructure,” said Dipankar Jha, senior sales manager, helicopters at Airbus India & South Asia.

Compare this to neighbouring Nepal’s 31 single-engine fleet used primarily for tourism, rescue, cargo transport, and medical evacuation. The country has 53 helicopters registered with the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal. Bhutan has three single-engine helicopters with a population of 8 lakhs. Bangladesh 40 for a population of over 17 crore.

Most helipads remain inactive or unlicensed, limiting UDAN’s ability to scale helicopter services where they’re needed most. Without functional infrastructure and better inter-agency coordination, expansion remains more aspirational than operational.

The Untapped Power Of Police Helicopters

Helicopters remain underused in Indian policing, despite their value for surveillance, crowd control, emergency response, and rapid deployment in remote or high-risk zones. Most state police forces lack rotary-wing assets due to cost, maintenance, and personnel constraints.

A few exceptions, like Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh, have piloted helicopter use for disaster relief and law enforcement. A tiered deployment model, starting with 100-150 helicopters in metros, border zones, and disaster-prone areas, could transform policing agility.

A Market Waiting For Lift

The broader helicopter market, including military and civil, is expanding fast. Helicopter import shipments grew at a 112% CAGR between 2020 and 2024, surging 43% just last year, mostly driven by defence orders. Civil growth, however, remains marginal.

Still, demand is building. India’s offshore oil and gas sector alone accounts for Rs 735 crore ($88 million) in helicopter services today, projected to reach Rs 943 crore ($113 million) by 2033. Tourism operations, valued at Rs 71.9 crore ($ 8.6 million) in 2023, are expected to double by 2035.

Each indicator points to demand that exists but can’t yet fly. Between policy rigidity and piecemeal planning, India risks missing a strategic mobility revolution. Rotor wings could connect what roads cannot reach—if the system lets them.

Missed Opportunity

Helicopters have quietly accelerated transmission and mountain infrastructure projects in India, especially in rugged zones. Companies like Sterlite Power, Power Grid Corporation, and Himalayan Heli Services have used them to slash timelines, cut land disruption, and reach inaccessible sites — from Madhya Pradesh to the Northeast.

Yet adoption remains limited, held back by high costs, fleet shortages, regulatory hurdles, and a lack of trained crews. With viability gap funding, relaxed airspace norms, and inclusion in infrastructure tenders, India could unlock a high-efficiency tool for its next wave of grid and high-altitude development.

Helicopters also reduce environmental disruption and improve worker safety, especially in forested, hilly, or disaster-prone areas. With the right policy push, such as viability gap funding, relaxed airspace norms, and inclusion in infrastructure tenders, India could unlock a high-efficiency tool for its next wave of grid and mountain development.

India’s civil helicopter industry has all the elements that it needs to take off but remains weighed down by fragmented policy and skeletal infrastructure

Rohini Chatterji is Deputy Editor at The Core. She has previously worked at several newsrooms including Boomlive.in, Huffpost India and News18.com. She leads a team of young reporters at The Core who strive to write bring impactful insights and ground reports on business news to the readers. She specialises in breaking news and is passionate about writing on mental health, gender, and the environment.