After Ratan Tata: A Leadership Void at the Heart of the Tata Empire

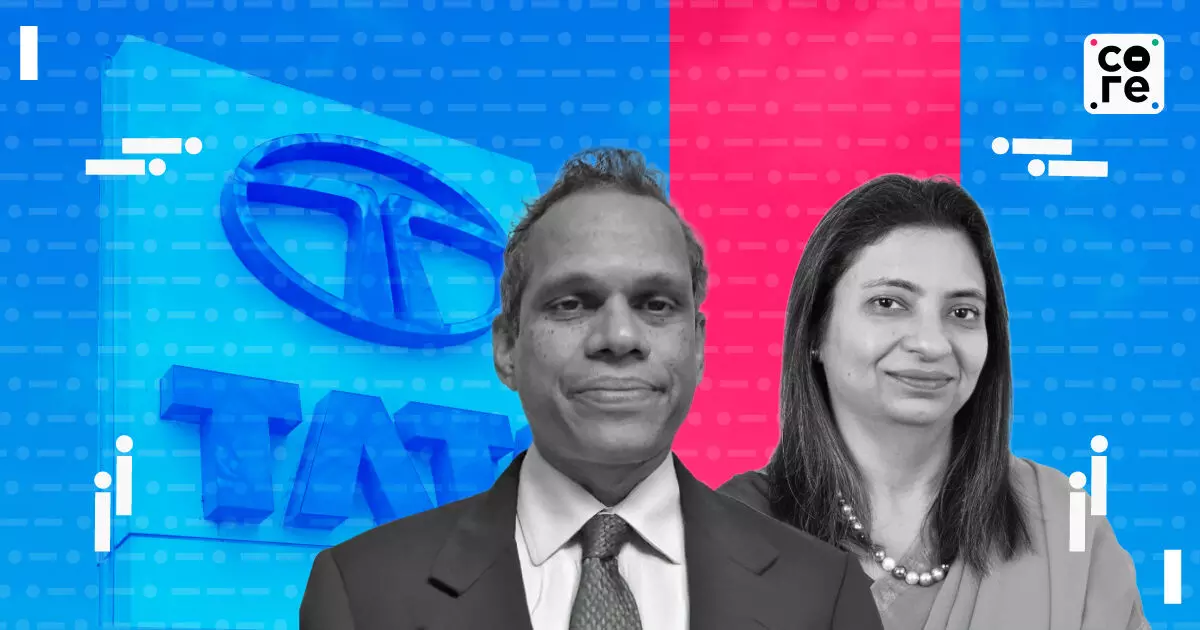

In this week's The Core Report: The Weekend Edition, Govindraj Ethiraj speaks with Shriram Subramanian, Founder and MD of InGovern Research Services and Hetal Dalal, President & Chief Operating Officer Institutional Investor Advisory Services India Limited, onTata Trusts’ rift that shows how legacy-driven leadership without succession or strong governance can unsettle even India’s most stable conglomerates.

NOTE: This transcript contains the host's monologue and includes interview transcripts by a machine. Human eyes have gone through the script but there might still be errors in some of the text, so please refer to the audio in case you need to clarify any part. If you want to get in touch regarding any feedback, you can drop us a message on feedback@thecore.in.

Hello and welcome to the Core Reports weekend edition. We've all been reading or hearing about Tata Trusts, the company or the institution that holds about 66 percent of Tata's sons, which in turn holds shares in many companies that we're all familiar with, household brands ranging from Tata Motors to Indian Hotels to Tata Steel and so on. Now, there have been fishers on the board of Tata Trusts for some time now and that has come out in the open. The question really we are asking today is first to understand why is this important, why is what is going on at a trust or a trust something that controls something that which in turn controls companies that are listed in which maybe some of us have stakes.

Why is this important? Secondly, what's going on in these trusts right now that should be of material relevance to those who are watching it from outside, if at all? And thirdly, what does this mean in terms of the governance structure of Indian companies or Indian organisations and whether this holding company format which we are seeing in this case or play out in this case is right for the present and the future?

So, that's really the three questions that we want to address with Sriram Subramanian and Hetal Dalal. Thank you both for joining me. So, Hetal, let me start with you.

Firstly, if you were to explain to someone who does not know what's been going on so far, because most of it is really removed a few layers from what could be, let's say, seen at a board level of a company, how would you explain that?

Hetal Dalal

If you look at, I think, first to understand the nature of the beast or to understand essentially the way the structure works. So, essentially the Tata Group has a fundamental foundation in philanthropy. The trusts are the ultimate shareholders, so to speak, of the group.

But at the point in time that the trust was set up, the regulation did not allow trust to hold equity in listed companies. So, therefore, they created a layer of Tata Sons, which was a private company which held equity in the listed companies. And that by creating this layer of Tata Sons, they essentially were able to navigate the regulatory requirements and therefore build this entire group.

Now, what is happening today is a dispute among the trustees for a set of reasons which there are several reports about. But to be fair, the trust has actually not really brought out any clarity on what's really happening. So, there is this whole executive committee of the trustee, which comprises four people, which is Noel Tata, Venu Srinivasan, Vijay Singh and Meli Mistry.

And they are essentially the representatives of the trust in terms of the trust and the trustees in terms of taking decisions with respect to Tata Sons. Noel Tata, Venu Srinivasan are on the board of Tata Sons. Vijay Singh was on the board of Tata Sons, but his reappointment with Tata Sons was not approved by the trustees and therefore he had to step down.

So, now essentially you have a vacancy on the Tata Sons board. So, the first issue which seems to be up for debate is really who's going to get that seat, who's going to represent the trust on the board of Tata Sons. The second issue seems to be how is Tata Sons really doing capital allocation and that seems to be something that the trust disagree with.

Now, to be fair, we've seen the trust having an opinion on the Tata group in the past as well. This was the whole sort of simmering background because of which you had this entire episode with Cyrus Mistry as well. And we see this now coming back again.

So, at one level, it is a trust trying to figure out how do they influence some of the decisions of Tata Sons. And I think that's, at the other level, there is also what would call it a leadership challenge. You know, Ratan Tata, when he came into the seat of power, faced a leadership challenge having to deal with some of the satraps there in the group.

And you now have Noel Tata having taken over from Ratan Tata as the chair of the trust. And that itself seems to be causing a certain degree of leadership challenge. So, I think that's really where it is.

Now, does it impact the listed companies? It doesn't. At this stage, it doesn't.

Let's put it that way. Because the listed companies are still concerned with how Tata Sons is operating because that's the holding company for them. And, you know, Chandra's got a reappointment for a third term.

He continues to be chair of the material subsidiaries of the Tata Group, the larger listed companies. And Tata Sons itself, yes. And to that extent, I think at the operating level for the listed companies, at this stage, I don't see an impact.

But we'll have to see how this entire feud sort of goes forward and what implications there are.

Right. Sriram, you know, talk to us a little bit about the structure itself, you know, the foundation holding a company, which in turn is holding stakes in other companies. Now, are there similarities or parallels to this elsewhere in the world?

And if so, what could we or should we be learning, if anything?

Sriram Subramanian

So, usually in a capitalist kind of structure, globally, there aren't many conglomerates which have this very charitable organisation owns a substantial portion, which is 66% of a capitalist entity like Tata Sons and subsequently operating companies. This is a construct of about 100 years now. Of course, people like Zim Premji Foundation in Bangalore has transferred shares to Bill and Melinda Gates, IKEA Foundation, for example, all these are entrepreneurs who subsequently transferred their shareholdings to sort of charitable entities, so that they derive even Warren Buffett is doing that, etc.

So that the fruits of capitalism flow to charitable organisation. But here in the Tata Sons and Tata Trust case, the entrepreneur is no longer there. I mean, who started Tata Jamshedji Tata Ji is no longer there.

And the problem is now that of diffused control, who controls really the Tata Trust. And that is where as Hetal said, is it a fight for control of Tata Trust and internal control of Tata Sons that needs to be seen.

Right. Okay, Hetal, so there are two parts to this, as we try and separate it. So there is Tata Trust, which was always held in a concrete and solid way.

There was never any problem about lack of control or fissure within Tata Trust, which sits above Tata Sons. Tata Sons, as we know, there has been an issue because there's the Palanji, Shapurji Palanji family, which was represented by Cyrus Mistry till he passed away. And he also was chairman of Tata Sons for a while.

And, and there have been clearly issues there. But we'll come to that in a moment. But tell us about Tata Trust itself.

Is there anything that, or rather what could have or what should have maybe caused the fissure that we are seeing now in a somewhat public way?

Hetal Dalal

So it looks like there are camps and factions, right? And that's not necessarily, if you reach a stage of being on the, on the trusteeship or the board of, you know, the largest group and the ultimate shareholder, I think the issues have to be beyond personal grudges and personalities and has to be more about the issues. But I think at this stage, what's happening is it's the entire battle seems to be getting caught up in the personalities.

And I think that's really where the challenge is. So mainly Mistry has been ousted from the, from the trust, while at some point he was a close confidant of Ratan Tata. And you know, all of these relationships are at somewhere family relationships.

Mainly Mistry is related to the, Palanji is, Palanji is, there's, you know, Noel Tata and Noel Tata, Ratan Tata. So there is also, there's entire complicated family relationship, which are also at play as an undercurrent. I think these are things which need to be addressed in a structural format.

See what's happening now, because of the personalities, there is this entire unsettled situation with the Tata Trust and it's now all over the newspapers. And there is no clarity from the Tata Trust, something that they should sort of communicate a lot more in terms of how they're addressing some of these differences. But I think that it seems to be more of a personality and family underlying current, undercurrent, which seems to be going on, which is sort of overlaid by the fact that there is this whole concern over capital allocation and board seats at Tata Sons.

Okay, so Tata Trust owns 66% of Tata Sons. Now, Tata Sons is not a publicly listed company at this point. Now, what can Tata Trust do or not do if, let's say, it has problems with the way Tata Sons is functioning or any other issue?

Hetal Dalal

See, it's as much as a controlling shareholder, right? In the sense that you have board representation. There used to be three board nominees on the board of Tata Sons, with Vijay Singh going out, there are two.

You have board representation, use that board representation to therefore decide how capital allocation is going to be made. I think this backseat driving and the power struggle at the back end is really what is causing a lot more of uncertainty and this is basically unsettling for everyone. So if there was a more harmonious relationship, I think being on the board of Tata Sons and therefore leveraging that would be a better way of handling some of these differences.

Right. My question is, and I'll come to the capital allocation bit, that there is nothing that Tata Trust can do instantly. Suppose Tata Trust owned shares directly in, let's say, Tata Steel or Tata Motors or Titan and it felt agreed for some reason, it could just sell the shares.

In this case, there's nothing to sell and there's nothing it can do expeditiously.

Hetal Dalal

No, it isn't. And I think therefore, you know, even if you look at Tata Trust, I looked at the annual report of the trust, the total disbursements in FY25 was 900 crores. It's not a very large trust.

If you just look at it, you know, TCS's own CSR spend will be more than 900 crores. And most of the other foundations will be larger, Reliance, ICSR, I'm pretty sure are going to be larger. So it's not a very large trust.

I think they're living off the dividends and that's definitely dividends in CSR. They're living off the dividends of the Tata Group and that's where they feel the crunch. But at the end of the day, there's nothing they can do expeditiously. So this seems to be more like personality clashes.

It's not something they can change tomorrow. And if Tata's board has decided on a certain capital allocation, there has to be a rationale behind it, which is, you know, which seems to be working for the group at this point in time, at least.

Right. OK, let's come to that. Sriram, if you want to pick up on that. So why is there an issue? And again, we've been seeing reports. So let me not list out each one of them. But why is there an issue or the discussion of capital allocation or capital raise right now?

Sriram Subramanian

At one end, Tata Trust has a veto power on the board of Tata Sons. Two is some of the trustees felt that they were not privy to the decisions taken by Tata Sons and some decisions were taken without their consent or without their information. So I think so this goes back to faulting Mr. Ratan Tata to some extent, because Mr. Ratan Tata was not on the board of Tata Sons. Yet this, not many commentators have said this, but Ratan Tata was endorsing most critical decisions, not just even by Tata Sons, by even the operating companies. OK, so this issue of if some father figure whose blessing is sought for key decisions, that comes to the root of it. So why does a company like Tata Sons need to convey all its decisions to Tata Trust or the trustees of Tata Trust?

They don't need to, as long as there is something which is defined in the articles of association where anything more than 100 crore investment, any strategic partnership or strategic investment like in semiconductors, etc. Those needs to be endorsed or approved by the trustees or the veto vote by Tata Trust. Yeah, that is fine.

But beyond that, why are you as trustees seeking specific information on the workings of Tata Sons? So that is, I think, the operating structure which had not been unresolved and that was also one of the reasons why there was a rift between Ratan Tata and Cyrus Mistry because Ratan Tata probably believed that every key decision at Tata Sons needs to be blessed by him. And unfortunately here, even at the time of his demise, this tension or this issue had not been resolved.

And Ratan Tata should be faulted for not ensuring a smooth succession plan at Tata Trust also because though he left a will and the successor was not appointed ahead of his demise, there was no grooming for that role, etc. etc. All these come to the bear now.

Okay, so we're going to come back to this issue of succession and preparing for it because this obviously comes up a lot across Indian families and Indian business families who of course own most of Indian business as well. Hetal, you know, so as per Sriram, it's not the specific capital allocation issue, but the larger issue of how it was operating, which is that you had a Ratan Tata who was blessing, to use his terms, transactions or initiatives, and either that was operating in an informal or informal with a formal overlay or formal with an informal overlay. So what should we be looking at now in the context of Tata Sons now? What are the issues at play?

Hetal Dalal

See, I mean, it worked earlier where you had a common chair, right? JRD was the chair for the Trust as well as the chair for Tata Sons, it worked beautifully. The minute they split that, it didn't really work very well. But in today's context…

You have Noel Tata at the Trust and Chandrasekharan at Sons, right?

Hetal Dalal

Yes. So again, this continues that the chair of the Trust is not the same as the chair of Sons. And I think markets also evolved and governance structures and expectations are also very different now.

And therefore, for us to say, for Tata Sons to be a board driven sort of company, there has to be a certain degree of acceptance about the decisions of the board made. And therefore, for the Trust to really have their representation on the board and use their rights as board members or as you know, dominant shareholders is the best way going forward. I think the structures that we're seeing now where you know, trustees are appointed for life.

You don't really allow that in listed companies, right? And listed companies regulation itself says every five years, you have to come up for a reappointment. So these positions for life, this whole permanency and this battle for who's going to be on the board of Tata Sons, I think all these are distractions, the governance structures at least at that end of the Tata group now needs to behave more like what you would see in listed companies, given the fact that the end goal of all of this is the fact that you're controlling a very large group and a lot of these companies are listed. I think that's the way going forward.

And if you were to take an illustration, you know, so let's say Tata Sons today, as you said, is one seat empty. And that's the seat that Tata Trusts could potentially nominate and have nominated. How could that operationally affect, let's say, one of the companies that is listed, and is about to do something or is planning something?

Hetal Dalal

See, I think it's as good or as bad as having an MNC, right? You have a global parent, which is going to decide capital allocation for an India listed entity. You look at essentially the same structure that you have now a parent company, which is going to decide capital allocation based on that you're going to make your own plans.

And if you don't get enough capital from the parent, you essentially try and raise money from the market because you're essentially a listed company and a lot of them are sort of index stocks. So to that extent, the reliance on, I mean, even if you look at the group, right, the reliance on Tata Sons has been when there was a very high, very large need to unlock capital. You know, if you look at the past 10 years, they basically reduced all their cross holdings.

They pumped capital into companies which were growing new businesses like Tata Motors. They pumped capital into Indian hotels. So that's the larger role of the group to say that, you know, I'm doing, I'm managing the capital across the group.

But a lot of these companies are standalone large listed companies and they can raise capital just as much as everybody else does, right? If you look at Tata Sons shareholding across the group, it's not a dominant 51 or 75% shareholding. In most of the companies, it's actually around 35%.

And therefore, for a lot of these companies independently, also, they can easily operate just like every other company does.

Right. Okay. So within Tata Sons itself, there is another, I mean, another conflict of sorts, because, I mean, at least there has been because there's the Shapoji Pallonji family with 18% and with some say in what goes on.

Now, my question really is, why is this again brewing? I mean, what is driving the tension that we are seeing right now, at least at the Tata Sons level?

Hetal Dalal

See, it's a bit unfair in terms of what's happening to the Shapoji Pallonji group, right? They clearly are strapped for money. I think they have a problem with debt.

And the Tata Sons equity is actually the most valuable asset at this point in time. But the Tata Sons isn't allowing them to pledge the shares, isn't allowing them to sell the shares, right? And isn't allowing them a boat seat either.

So therefore, you know, you're essentially trying to corner a material shareholder with a relationship with the family for generations, right? I think that's a bit unfair. Tata Sons has to find an honourable exit for the Pallonjis and do something with that 18% equity.

Either they buy over the equity at a reasonable valuation, or they get a new partner who will buy over that equity at a reasonable valuation. Or then you list and let the shares be sold. But you have to give them an exit option.

I think the problem and the simmering tension continues because you're not giving them an option. They really want to exit at the end of the day.

And is there anything preventing the exit from a technical standpoint? Or preventing the going public?

Hetal Dalal

Yeah, I think the way the entire structure was formed, right, I think the intention was never for the Pallonjis to exit. I don't think that was baked into the initial thinking. And now that they've become a private limited company, and they're creating all these sort of limitations to the Pallonjis from being able to exit, they even went to court saying you can't sort of pledge the shares.

I think that's where this is becoming a bit unfair in terms of treating a shareholder who wants to exit and a material shareholder at that.

Sriram, is this your reading as well, that the core of this is really a financial problem or an issue that has to be addressed by one of the shareholders, and therefore, they want a quick way out?

Sriram Subramanian

That's one of the dimensions for sure. Because if Shapurji Pallonji Group, I mean, if you look back in history, it says that Shapurji Pallonji Group actually bailed out the Tata Group at that time, right. And if it were a VCPE kind of firm, it would have structured an exit option for itself.

And it would have been the largest decision maker in terms of putting a stop, having negative and positive covenants in the shareholders agreement. Unfortunately, at that point of time, the SP group trusted whoever was on the other side of the negotiating table. And as Haithal said, they're caught now in that sort of history.

And unfortunately, the Tata sons and the Tata trust are not allowing Shapurji Pallonji a graceful exit. Okay, one way, of course, is to list Tata sons, at least RBI is pushing for that. And so that would at least give liquidity to the shares of SP group, and they can pledge.

Or two is Tata sons could have allowed a pledging of shares of the SP group. Three is or buy out in some other way, or whatever it is, right. But they have completely blocked it out.

And this is also probably the ego clash that happened with between Ratan Tata and Cyrus Mithri and led to this over the past 10 years since 2016. So unfortunate as it is, SP group, though it requires the money and the funds is caught in this, where their largest asset is and they are not able to exit it. And so Tata's need to, that is probably their weak link.

In that sense, one cannot say that they are honourable from that perspective. So to that extent, they need to work towards it. Otherwise, they will always have this black mark on their, whoever, the board, and trustees and everyone out there.

Right. Haithal, we have many business houses in India, which have some form of holding company. And none of them are listed or most of them are not listed.

What do you feel about the concept of a holding company getting listed? And is that could that be also a cause of tension that you know, once you list a company, which is the holding company that then there is potentially the chance that you might lose control at some point and maybe that's what's causing the friction here.

Hetal Dalal

Actually, if you look at there are a handful of companies which are holding companies and are listed. And essentially, what happens in those structures in most instances, they are not. Very closely held.

Well, the holding companies, if the promoters through the holding, listed holding company are able to exercise far more control than their economic interest in the operating company. And I think that's the structure which we see. The holding companies tend to operate, of course, at a holding company discount.

So we have seen these structures, holding companies are listed in India. I think as far as the Tata group is concerned, my understanding is that TataSense doesn't want to be listed. They're doing everything they can to not get listed.

But if they do get listed, what happens for them is that the degree of transparency required will be significantly higher. There will be far more public scrutiny of the decisions they make, which I don't think they want to subject themselves to.

And Sriram, is that something that's a natural path? You know, like a holding company, as we've now talked about, has been around for a long time, close to a century, and then, you know, getting listed, opening up to public scrutiny. Is that a natural path?

Or is it something equally quite natural to resist?

Sriram Subramanian

No, I would think it's natural to resist for them. But because they are not providing liquidity to the SP group, probably they need to work towards that. Or they should sort of diffuse their shareholding in the listed entities separately and unlisted entities, somehow give some part to the SP group.

Otherwise, there will be that tension of TataSense to be pushed for listing. Even the SP group put out a statement saying that they are pushing for the listing of TataSense, right?

Yeah, right. So if I were to look at what we can learn from this for future in the context of family-run businesses. Hithal, let me start with you.

So we've talked about, you know, the fact that there is obviously friction at the Tata Trust Board, which has now come out into public domain. So that, I guess, is the first problem. The cause of this is potentially egos, potentially some other misunderstanding, and so on.

But that has now translated into a corporate situation. What is the takeaway from this, from a governance point of view, even as we look at or examine other family-run businesses and family-run businesses with such similar structures?

Hetal Dalal

Well, look, we see a lot of inter-promoter group disputes, right? Last year, we saw several. And I think the big, and that happens when generations change, typically.

That is the first and second generation, you're okay, because the first and second generations have built the businesses. When it comes to second and third and third and fourth, that's where the different agendas of individuals sort of start becoming, contradicting each other, let's put it that way. And therefore, there needs to be one, just a family constitution in terms of how the equity is going to be handled.

Are you going to be in management control? And who's going to be in management control? And if you're not going to be in management control, what do you do with your equity?

How does it go down from generations to generations? And what is the fundamental philosophy you will have as far as the company is concerned? I think these are things which need to be sorted while the patriarch is alive or the matriarch is alive.

Some of the groups have done it well. The Bajaj group has done it well. Heroes have done it, you know, the Munjals have done it well.

And they've managed to create the family arrangement while, you know, the matriarch and the patriarch are alive. And I think that's what's now you'll see as a seamless operation. But when it doesn't come to that and you don't have that clarity, I think that's where the issues sort of creep in and begin.

And I think that's really where companies need or families need to focus more in terms of how they deal with the next generation. And sometimes it's about hard conversations about saying, you know, are you really up to it or are you not up to it? You know, just because you belong to the family, you may not have the calibre to run the business or take it from point B to point C, as much as you know, the initial promoter took it from point A to point B.

So I think that's really some of these difficult choices that families need to make. But it's good to have that conversation when everybody's around and there's clarity and everybody accepts, rather than subsequently in a will written somewhere, where everybody...

In the case of Tata Trust or Tata Sons, Hetal, this, I mean, literally happened a century ago. I mean, the patriarch has passed on. And I guess the question there is, how do you lay down the structure so that someone who comes 50-60 years later, or directors who come 50-60 years later, or the person they elect as their chairman, or chairperson 50-60 years later will be following a certain set of principles and not get into this kind of public squabble?

Hetal Dalal

Yeah, it's a tough, it's a, it's a tough idea. See, the way to look at again is that, you know, leadership will change or leadership, corporate culture changes with leadership changes, right, that we see in almost every company. And the idea, therefore, is how do you build a certain ethos in the system to ensure that there are certain do's and don'ts, which will always happen.

And that happens through basically building a very strong culture. What's happened now is that the operating companies have a certain Tata Group culture. Your fundamental problem now is that the trust and the Tata Sons level, that's the relationship which is not as smooth as it should be.

And that's a function also how the trusts have been run for a long time, right? It's been Mr. Tata or it's been a controlling patriarch, which has basically run the trust. So to have a more functioning board structure per se, to be able to, you know, manage the trust agendas is what they need to sort out.

So I think that governance structures of trust, despite the fact that yes, trusts have other rules, and they don't have to necessarily follow what listed companies follow. But it's working well for listed companies. And the fact is that they are the ultimate shareholder of a set of very large listed companies.

So they need to now operate with those kinds of governance structures and mechanisms, more importantly, you have to process clarity and all of that.

Right. And that's the point you made at the outset as well. Sriram, let me come to you.

So if you're now advising an institutional, large institutional investor in one of these companies, Tata Motors or Tata Steel, is this a matter of concern at a Tata Motors level or a Tata Steel level? Or is it something that you would wait to see how it pans out and then maybe start asking questions at a later stage?

Sriram Subramanian

No. As such, these, there are 26 listed operating companies. I don't think investors need to be unduly worried as of today, because even their decisions have to be, because Tata Sons is just one shareholder of the many shareholders.

And as HL said ahead in some of these operating companies, the Tata Sons owns only about 30% or 35% shareholding. So from that perspective, not all decisions are their own, I would say, this one. So what is happening at the trust level is not directly impacting the operating companies in any matter today.

But if it gets very, very nasty, and something happens in future, which is not foreseen, obviously, investors need to watch out and be aware of what is happening. But they don't need to unduly worry today.

Right. And, yeah, go ahead, Hetal.

Hetal Dalal

No, I just want to add to what Sriram was saying. At the end of the day, right, the Tata group is known for a certain, there is a basic expectation in the brand that there is a certain governance structure, there is a certain degree of integrity of operations. But you don't, with all these instances which are coming out in public domain, it's also chipping away at the brand.

And that's something that the trust also needs to recognise that some of these things, either you provide clarity and transparency, or you know, you have to sort of nip a lot of these in the bud, you can't get to a public level, you have this whole Cyrus mystery issue. Now you have this entire issue. So I think this is not necessarily good for a brand, which is essentially known as being extremely trustworthy.

Right. And Sriram, last question. So as we, you know, this is obviously a market, which is quite vibrant, I'm talking about the capital market.

As both of you say, I mean, currently, we're a few layers removed from what's going on. And therefore, there is no need to get worried, so to speak. But is there anything else that you would should be or would be thinking about?

When it comes to this sort of holding company structure? As we look ahead, should people be thinking of these structures differently in future? For example, and that's really my last question.

Sriram Subramanian

Yeah, I think one should avoid conflicts of interest between individual members of the board or trust, and the business entities, I believe that there are business interests of each of the trustees, and are there are even some of the directors, etc. So these conflicts of interest should be totally run down to zero. Otherwise, Meli Mistry is supposed to have contracts with some of the operating companies.

And those kinds of things that should be nipped in the bud. I mean, on day zero, it should be if you're a trustee, you should not have any business. Only then will people take independent decisions of independent of their business interests.

Hetal?

Hetal Dalal

No, I'm with Sriram on this, I think.

No, the question is really so are these structures fine, but really the people issues that have to get resolved, including maybe some of these related party kind of transactions and so on? Or is the structure itself should one question?

Hetal Dalal

See, my general view is that the structure is as good as it gets if the people run it efficiently. I think for the longest time when JRD Tata was around and there was a seamless, you know, similar chair, it was running efficiently, right? And every structure that you create will, will create problems in terms of no structure is perfect.

Let's just put it that way. No structure is perfect. The Tata group is a unique structure, you don't see it often, and was created for a certain underlying philosophy of the group.

I think it's a lot about how people manage it. And as Sriram says, right, that if you have a bunch of people at the trust level who are purely focused on getting the story together and figuring out what the underlying philosophy is, and being issue based, I think this would run far more smoothly, what you're seeing now are undercurrents of relationships, personalities, and agendas.

Right, Hetal and Sriram, we've run out of time. Thank you so much for joining me.

Hetal Dalal

Thank you.

Sriram Subramanian

Thank you.

In this week's The Core Report: The Weekend Edition, Govindraj Ethiraj speaks with Shriram Subramanian, Founder and MD of InGovern Research Services and Hetal Dalal, President & Chief Operating Officer Institutional Investor Advisory Services India Limited, onTata Trusts’ rift that shows how legacy-driven leadership without succession or strong governance can unsettle even India’s most stable conglomerates.

Zinal Dedhia is a special correspondent covering India’s aviation, logistics, shipping, and e-commerce sectors. She holds a master’s degree from Nottingham Trent University, UK. Outside the newsroom, she loves exploring new places and experimenting in the kitchen.